In One Small Room, a World of Emptiness

BESLAN, Russia, sept 28, 2004 : Every morning, Vova Tumayev sets the breakfast table for three — husband, wife and adored 10-year- old daughter. Nobody eats. Mr. Tumayev sits alone for a little while, then clears the table.

His wife, Zinaida, and his daughter, Madina, died in the seizure of a schoolhouse here at the beginning of September, two of the hundreds of victims of an attack linked to the war in Chechnya.

There is nothing Mr. Tumayev can do — no ritual, no act of mourning — that can begin to fill the emptiness their loss has left behind. At night, he said, he sleeps in his daughter’s bed.

“They say ‘Aren’t you scared to do that?”‘ said Mr. Tumayev, 44, a plumber. “I say I’m not afraid of anything. But it’s true, whenever I lie there some strange things come into my eyes.”

As the people of this little town struggle with their grief, the schoolhouse where their children died has become a place of echoes and memories as well. Hollow and filled with rubble, it is piled with wreaths and offerings, with messages of condolence scribbled like graffiti on its walls.

Mr. Tumayev is just one lonely mourner in a town where thousands of people are bereaved.

He married rather late, at the age of 34, to a kindergarten teacher, and the warmth of having a family, here in this little bachelor’s apartment, continued to fill him with astonishment and joy.

“I gave her everything she asked,” he said of his daughter. “I never said no to her.

“My wife said, ‘Be strict with her so she’ll obey you,’ but I couldn’t. Sometimes my wife scolded her. I never did. When I came home from work she’d run out and hug me.”

Already, he said, friends are urging him to move on once the traditional mourning period is over, as if the past could possibly be left behind.

“They tell me, ‘After 40 days, go marry again,”‘ he said. “But even if I marry again 10 times I’ll never have a child like that. How I loved her, how I loved her.”

He picked them out immediately in the morgue, he said, although their bodies were charred and grotesque.

“My daughter was shot in the head,” he said. “One leg was off, the other was barely joined to her body. Her face was so burned you couldn’t recognize it. I just recognized her earrings, and a bit of her hair, and immediately I knew it was my daughter.”

“People were saying, ‘Maybe it’s not her,”‘ he said. “They had numbers on them, and I said, ‘Write that number down.’ I knew them right away.”

Mr. Tumayev has set up a little shrine at home, a table piled with bananas, apples, dried fruits, biscuits, and his daughter’s favorite sweets.

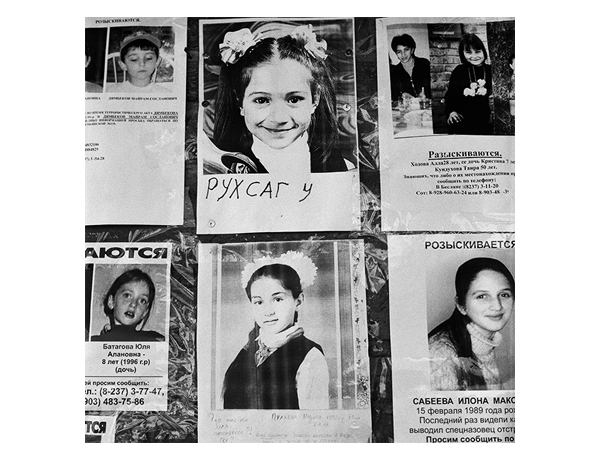

His apartment is filled with pictures of her, just as the walls of the schoolhouse are pasted with photographs of missing children — each one a reminder of her absence.

He took a small album of photographs from a shelf and began turning its pages one by one, explaining each picture to a visitor as he went.

“That’s her,” he said, showing a picture of a smiling girl in a red dress. “That’s her, that’s her, that’s her at the beach; that’s also her and here she is, here she is, here, here she is; there she is in the countryside, there also, and that’s her, too.

“Oof, this is difficult,” he said, but he kept turning the pages.

“There she is in Rostov, there she is, too; there she is with her mother; there she is, she was tall, almost as tall as me; that’s her, too, and that’s her, too, and that’s her, and that’s also her, also her, also her; there she is with her friends, that little girl died, too, there she is waving.”

“Everything in here is her,” he said, handing the album to his visitor. “I don’t want to look anymore.”

Copyright The New York Times