Their Lives Consumed, Officers Await 2d Trial

LOS ANGELES, Feb. 1, 1993 ; Three little girls were playing tag in the living room, a small white dog was barking happily and Sgt. Stacey C. Koon, who goes on trial on Wednesday in the country’s most celebrated police-brutality case, was rolling around on the rug, demonstrating the actions of the man who was beaten, Rodney G. King.

He had just narrated for a visitor the videotape of the March 3, 1991, beating on his large-screen television set, eager to explain, to justify, to defend each baton blow, and he was gripped again by the excitement that overcomes him when he is making his case.

“If we had our way, we’d go down to Dodger Stadium and rip off that big-screen Mitsubishi and bring it into the courtroom and say, ‘Hey, folks, you’re in for the show of your life,’ ” he said, “because when this tape gets blown up it’s awesome.”

Sergeant Koon is one of four officers who face Federal civil rights charges in the beating, and like his fellow defendants, he has become obsessed by the videotape that has made them symbols of racism and police brutality, unable to talk or even think about almost anything else.

Last month, in long separate interviews just before their trial, three of the four defendants seemed to find relief in talking about their obsession, about the physical and emotional ailments that beset them and about their desperation at being trapped by history, condemned to guilt in the public mind no matter what the jury’s verdict.

Although their lawyers may have sought an advantage in presenting the defendants as something more human than videotaped images of men with batons, it was clear from the interviews that the officers’ own belief in their innocence, and even victimization, was desperately heartfelt.

But whatever their defense, these are the men who shocked television viewers around the world as they repeatedly clubbed and kicked a mostly prone black man, then dragged him, hogtied, to the edge of the road.

“To be portrayed as a bad guy when really I am a good guy, that’s probably the most upsetting thing in this whole affair,” said Officer Laurence M. Powell, who is shown on the videotape delivering most of the 56 baton blows.

“I don’t want to read about myself in a magazine or in a history book as a symbol of racism and police brutality,” he said. “That’s real disturbing to me. But there doesn’t seem to be any choice in the matter. It’s going to happen.”

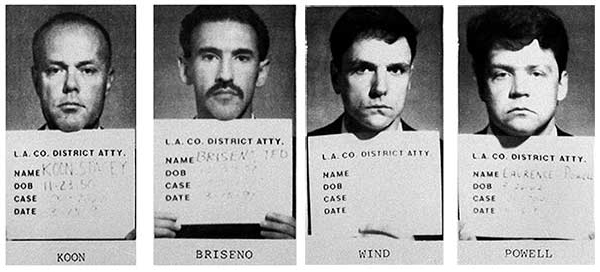

The four officers, Sergeant Koon, 42 years old; Officer Powell, 30; Officer Theodore J. Briseno, 40, and former Officer Timothy E. Wind, 32, were acquitted of assault charges last April 29, in a verdict that touched off rioting in which more than 50 people were killed. Now, if convicted on Federal charges of depriving Mr. King of his civil rights, they face possible sentences of 10 years in prison and fines of $25,000.

All but Mr. Wind agreed to be interviewed about their lives in advance of their second trial, offering the most intimate glimpse they have given into their lives. Only Officer Briseno spoke in the presence of his lawyer.

“You have to understand that I did two things that evening, just two things that the video shows,” Officer Briseno said. “I grabbed the baton of Powell, and I put my foot on Mr. King and tried to hold him down. Is it fair for me to go through all this? I don’t really think so, for doing two things, two little things.”

In pretrial documents, Federal prosecutors have indicated they plan to focus on Officer Briseno’s statements at the earlier trial, calling them perjury and evidence of a guilty conscience.

The prospect of the new trial terrifies him. “I keep asking myself the same thing: ‘God, why didn’t I just get in a car and get out of there?’ ”

Although a jury acquitted him of assault last April, Officer Briseno said he has continued to serve a sentence of inner torment.

“In the morning I take the children to school, and when I come home, I have a sort of routine as far as cleaning the house,” he said. “But there are those days when I come home and I just can’t function and I might just sit there all day and I don’t know it.

“Sure, it’s depression. Sure it is. Sometimes it’s just unbearable. I’m not afraid to tell you that I just sit and I cry.”

His wife is the breadwinner now, along with his 73-year-old mother-in-law, who he said had taken a part-time office job to help make ends meet.

Like Sergeant Koon and Officer Powell, he has been suspended without pay by the Los Angeles Police Department, pending a departmental hearing that will follow the Federal trial. The local police union, which covered defense costs in the previous trial, is helping with only part of the costs this time.

Mr. Wind, who was a rookie probationer riding with Officer Powell at the time of the beating, was dismissed from the force, and his fellow defendants say he has been hit the hardest emotionally.

“From time to time, he’ll just rant and rave about how horrible the whole thing is,” Officer Powell said. “At other times, it seems it’s just too much and he clams up.”

Sergeant Koon called it a classic story of a young man from Kansas who comes face to face with evil in the big city. “He came out here to be the best of the best in the L.A.P.D., and he gets into a situation where all of a sudden — wham! — ‘What the hell happened to me? Why can’t I just go back to the country where it was nice and simple and life was good?’ ”

The men have separate lawyers and separate defenses, and tensions arose among them last year after Officer Briseno testified in the first trial that he believed that Officer Powell had been “out of control” and that Sergeant Koon had mishandled the incident. But he has now changed his account and no longer blames his fellow officers, and Officer Powell said the defendants were trying to maintain solidarity.

Like Officer Briseno, who cherishes a boyhood memory of seeing a policeman saving a little girl from an angry dog, Officer Powell said he became a law officer to do good.

“From the time you arrive at the station to the time you drive back, the whole shift is usually filled with some kinds of satisfaction,” he said, “arresting a robber or arresting a guy who beats up his wife, or maybe you solve a problem between neighbors or you’re looking for a lost kid. It’s instant gratification. You feel like you’ve made some sort of difference.”

Though he said using force was not a source of satisfaction — “It never is, not to any officer, unless they really have psychological problems” — Officer Powell said he did get job satisfaction from the arrest of Mr. King after he was stopped for speeding.

“It certainly wasn’t pretty, no more than a police officer having to shoot somebody who walks out of a bank with a shotgun,” Officer Powell said. “It’s an ugly thing, but somebody has to do it.”

As Sergeant Koon put it: “We take Rodney King into custody. He doesn’t get seriously injured. We don’t get injured. He goes to jail. That’s the way the system is supposed to work.”

He added: “It is brutal and it is inhuman, but it is not excessive force and it is not police racism. Those two things are not on this tape. This tape is explainable.”

Or in the words of Officer Briseno: “I deal with Rodney Kings every night. All policemen do. He was disobeying the law, and I was trying to apply the law. The only reason this one stays in my mind is because of what I’m going through.”

All the officers say they have been suffering physically and emotionally since the beating — as has Mr. King, according to his lawyers.

“Yesterday, I got declared psychologically disabled for work,” said Sergeant Koon, laughing. “The only thing I can deal with is, I can deal with this case and I can deal superficially with my family. I can take my kids to school and pick them up.”

In addition, he said, “I’ve got sleeping disorders, I grind my teeth, I’ve got stomach problems, I’ve got headaches, I’ve got high blood pressure, I’ve just got this laundry list of stress disorders.”

To pay his bills, Officer Powell, who is single, sold his house and moved into his parents’ home, where his legal papers are stacked in cardboard boxes beside the glass case that holds his mother’s collection of dolls.

Since he was a teen-ager, his parents have taken in foster children, who are often members of racial minorities. Officer Powell points to this fact, and to the fact that his girlfriend is a Hispanic police officer, to rebut accusations that he is racist.

When he is not preparing his legal case, he said he has resumed his boyhood chores, helping diaper and care for the black girl and two Hispanic children who now share his home.

But for the most part, he said, “This trial is my life. I have nothing else. I go to sleep with it on my mind and I wake up in the morning with it on my mind. I have people say, ‘You probably don’t want to talk about this,’ and I say, ‘Gosh, I don’t know what else to talk about.’ ”

Sergeant Koon has spent the weeks before the trial at his dining room table, digging through 17,000 pages of legal documents to the accompaniment of endless, bouncy tunes from his children’s video games in the next room.

He wrote his master’s thesis on the evolution of the theory of policing, and he said he felt almost chosen by fate to play out the latest chapter in his own work. But he said he also realized that his obsession with the case was a battle for his sanity.

“Make no doubt about it. All four of us are in pain. And each person handles his pain differently,” he said. “People that go insane, they don’t want to deal with reality so they go into their own world. That’s why I go over these documents. There’s nothing in this case that I don’t know about.”

The large-screen television set dominates his living room, and Sergeant Koon cannot seem to stay away from it.

“There’s 82 seconds of use-of-force on this tape, and there’s 30 frames per second,” he said. “There’s like 2,500 frames on this tape, and I’ve looked at every single one of them not once but a buzillion times, and the more I look at the tape the more I see in it.”

He takes the tape with him on speaking tours, and on every new screen he sees something new in it. He projects it at home, trying one wall, then another, and he finds still more, in a never-ending search for new evidence, new explanations, new meanings.

“When I started playing this tape, and I started blowing it up to 10 inches, like I’d blow it up on this wall right behind you here, fill up the whole wall over the stairwell, and all of a sudden, this thing came to life!” he said.

“You blow it up to full size for people, or even half size, if you make Rodney King four feet tall in that picture as opposed to three inches, boy, you see a whole bunch of stuff,” he said.

And then, slipping the tape into his video machine, he offered his visitor a fast-paced, 82-second narrative, living through the beating one more time, laying out his defense.

“He’s like a bobo doll,” he said, pointing to the blurry figure of Mr. King. “Ever hit one? Comes back and forth, back and forth. That’s exactly what he’s doing. Get him down on the ground. Prone is safe. Up is not. That is what we’re trying to do is keep him on the ground, because if he gets up it’s going to be a deadly-force situation.”

His daughters were preparing for a church jog-athon as Sergeant Koon, energized once again by an examination of the videotape, led his visitor to the door.

“This is going to be fun,” he said, anticipating the trial. “This is high comedy.”

Copyright The New York Times