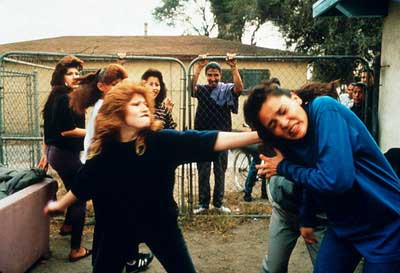

Life in Girls’ Gang: Colors and Bloody Noses

LOS ANGELES, Jan. 28 1990 : It was Shadow’s coming out party, her initiation into the Tiny Diablas girls’ gang in the Watts district, and she was dressed in the height of gang fashion: narrow corduroy pants, a sweatshirt in the gang color purple, extravagantly teased hair and exaggerated black-red makeup.

The ceremony was in Giggles’s backyard, behind two rusting automobiles, where there was some privacy from the curious young men who lounged nearby with members of their own gang and from the youngsters on roller skates who chased the armored ice cream wagon with its tinkling bell.

”Somebody hold my gold,” said Giggles, taking off her rings and wrapping a purple bandanna around her right hand.

Then, as 20 gang members counted off the seconds in a loud teen-age chorus, Giggles, Shygirl and Rascal performed the initiation they call a court-in, a 13-second beating that ended with tangled hair, smudged lipstick and a bloody nose.

Small compacts were opened. A can of hair spray was passed around. Rings were redistributed to their owners. Somebody produced a bag of Dorritos.

The court-in, which mimics the similar but often more violent initiation ceremony of male gangs, is an expected event in the childhood of many girls in the inner city. For girls like those in the Tiny Diablas, who range in age from 14 to 19, the gangs offer a social structure and sense of identity that members may not find elsewhere.

At her court-in, a girl is christened with the nickname by which she will be known and, as one former gang member put it, suddenly finds that there are 30 to 40 people ready to die for her.

If she fails to do her part as a loyal gang member – if she is not, as the girls say, down for her neighborhood -she can face a ”court-out,” in which there is no time limit to the beating.

A few days’ visit with the Tiny Diablas gave an unusual look inside this society, an odd mixture of teen-age ebullience and criminality that is all the more unsettling because of its atmosphere of normality here in the broken streets of Watts.

”Don’t you have gangs where you come from, too?” a gang member asked, puzzled by a visitor’s curiosity.

There are about 600 gangs in Los Angeles County with 70,000 members, the police say. Two-thirds of the gangs, like the Tiny Diablas, are Hispanic. About 10 percent of gang members nationwide are girls, said Anne Campbell, a Rutgers professor who wrote ”The Girls in the Gang,” published by Basil Blackwell in 1984.

But Michael Genelin, chief of the hard-core gangs division of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office, said women were involved in few of these serious crimes. Usually operating as affiliates of male gangs, they offer support in highly stereotyped female roles for the young men they call their homeboys.

”Violent aggression seems to be almost entirely a male prerogative,” Mr. Genelin said. ”I think there is a difference in role playing, in the picture that a male has of himself and the picture that a female has of herself.”

This may be changing somewhat, said Marianne Diaz-Parton, a former gang member who is now a social worker for the city. In a shift she compared with women’s liberation, she said girls’ gangs are beginning to stand on their own, to pick their own battles and to fight them more violently.

When Shadow’s court-in was over, the gang leader, an 18-year-old high school senior whose gang nickname is Tiny, announced that she would begin a weekly collection of dues to buy guns.

The 30 or so members of the Tiny Diablas are affiliated with a local male gang, the Grape Street Watts, but the girls said they wanted to become less dependent.

”Our homeboys won’t give us guns,” explained a 16-year old member named Shorty. ”They say we’ll get hurt. But we can’t depend on our homeboys all the time. We’ve got to put in for ourselves.”

Like many of the Tiny Diablas, Shorty was born to gangs. Especially in the Hispanic community, Mrs. Diaz-Parton said, ”Their family and their gang sometimes are one.”

Shorty’s father, a gang member, died of an overdose of heroin and was identified by his tattoos, which included one bearing her name. Shorty’s mother, also a gang member, abandoned her.

She lives with her grandmother, a gang follower in her own day, who says she has given up trying to discipline the girl because ”she gets all paranoid and starts cussing.”

Shorty’s aunt has one teardrop tattooed by her eye, signifying one year in jail; her uncle has two.

”These youngsters are looking at a future that is pretty depressing,” Ms. Campbell said. ”They are looking at a future in prison or drug addicted. With the girls a large percentage will end up unmarried and raising their children on welfare.”

Despite their own gang backgrounds, parents and siblings usually seem to discourage the girls from joining. Some of the Tiny Diablas said they would forbid their own children to take part in what they said is a hard and dangerous life.

Shadow’s court-in was performed quickly for fear that her brother, himself a gang member, would prevent it. When it was over, most of the girls hurried away because they had to be home before dark.

”Oh, I’m going to get beat up when I get home,” said Spanky, wondering whether she should tell her mother she had stayed after school for a softball game.

In the Grape Street area, the police are on familiar terms with the Tiny Diablas, stopping the other day as they cruised by to ask 14-year-old Tweety how she was doing in school and how the homeboys were treating her.

But an hour later, when a dozen friends had gathered with her on the street, the police lined them up against the hood of their car, searched for drugs and told them to disperse.

Tweety was first arrested a year ago for fighting at a movie theater. She says a knife that was found on the floor beside her was not hers. Soon after that she was arrested for driving a stolen car and she is now on probation.

Although Tweety said her mother’s reaction to her first arrest was, ”Oh, my baby, I never thought you would end up like this,” her mother has already stopped asking where Tweety goes when she leaves the house at night.

On the Saturday night after Shadow’s court-in, a group of the girls were not sure where they were going to go because so many of their homeboys were in jail.

”Whoo, my homeboy Zero is in jail, my homeboy Silent is in jail, my homeboy Rascal is in jail, my homeboy Night Owl is in jail,” said Shorty.

Tiny’s boyfriend is serving a six-year sentence for a gang killing. Sixteen-year-old Triste’s boyfriend has just written her from jail asking her to stay true to him. Fourteen-year-old Mousey’s boyfriend was arrested just last week for breaking and entering. Shorty sits up late at night writing to her boyfriend, who is in jail for auto theft.

Few of their friends are in prison for drug-related crimes. Hispanic gangs are not heavily involved with the crack trade, and their drug dealing tends to be well organized, with a minimum of turf wars, Mrs. Diaz-Parton said.

”There’s not that much drugs,” said Tiny. ”When we kick back, it’s mostly smoking, drinking, some weed, maybe some coke.”

The first stop tonight was Mousey’s house. A carload of girls gathered around the mirror in her tiny bedroom, where religious drawings share wall space with gang logos and where piles of stuffed animals, like their owner, are festooned with scarves and ribbons in Grape Street purple.

Fashion was high tonight: baggy boys’ trousers sagging over corduroy bedroom slippers, boys’ black polo shirts, large hoops in ears and bunches of keys and trinkets hanging from waists.

Lively chatter and clouds of Aqua Net hairspray filled the room as the girls applied dark lipstick, dark blush, black eyeliner and dark eyeshadow surrounded by white eyeshadow.

”They took Flaco last night,” said one.

”But they haven’t put him in the box?”

”What did he do?”

”Possession or selling. He ran from the police.”

”You do your hair fast, Mousey.”

It had started to rain when the girls emerged into the evening. Hunching their black jackets over their heads to protect their hair, arms in the sky, they shuffled quickly down the broken sidewalk in their baggy pants and corduroy slippers, their bunches of keys and trinkets jingling.

With the rain and so many friends in jail, the evening was mostly uneventful. The girls drove through Florence, a rival gang’s territory, and shouted, ”Grape Street Watts” out the window once or twice.

Saturday ended with an evening of girls’ talk at Giggles’s house, where Giggles lives with her aunt because her father is in jail for child molesting.

Copyright The New York Times