Playing Through the Pain: a Pianist's Struggles

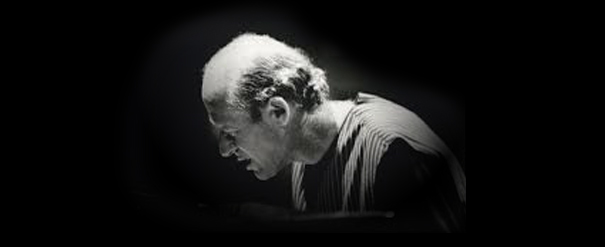

PENRITH, Australia, Jan. 14, 1997 : Shoes off, head bowed nearly to the keyboard, David Helfgott winds his way back and forth through the phrases of a Chopin prelude, singing, sighing, making buzzing noises with his mouth, talking to himself.

“Keep playing, keep playing,” he murmurs, his eyes half closed. “You’re playing nice now. Gentle. Gentle. La la la la. Just play every note and you’ll be fine. Smile, smile, smile. Image is everything. Image is everything. At least you’re playing well. If you’re playing well, you can survive now, so what’s this fear of the future? Zhhhhhhh.”

Transported by the music, he lifts a free hand to conduct himself and smiles.

This is a recording session, and the auditorium of the Joan Sutherland Performing Arts Center is empty, but Mr. Helfgott, 49, is hardly alone. The darkened seats are populated by his ghosts, and he plays to them.

”Papachka,” he says, referring to his late father, the man whose obsessive love and cruelty were inescapable elements of his upbringing. ”Papachka thought it should be different. Well, they like your playing. They like your playing. This is the point, the point, the point, if there is a point.”

In recent weeks, Mr. Helfgott’s troubled past has returned in force to transform his life.

A biographical movie about him, ”Shine,” is a critical hit $(on Sunday, Geoffrey Rush, who portrays the pianist as an adult, won the Golden Globe Award for best actor$), and suddenly Mr. Helfgott is at the center of attention. He seems to love it.

He is here in the darkened auditorium, recording tracks for a second compact disk of his music, and as soon as he stops playing, he is surrounded by his manager, his piano coach, his wife and a television crew that is preparing a report in advance of an American tour beginning in March.

Mr. Helfgott has stopped playing, but he remains in motion, shuffling rapidly from one person to another like a fly bouncing from one lighted windowpane to another, hugging, kissing, chattering as he goes.

”Awesome, awesome, America is awesome,” he murmurs. ”You’ll be fine. You’ll be fine. The worry’s the killer; the worry’s the big killer, isn’t it. O. J.’s a killer. Don’t worry. Don’t worry.”

Mr. Helfgott’s wife and protector, Gillian, called his new popularity ”a victory over the past” and said it seemed to have lifted some of the burden of pain from his shoulders.

”Genius and madness,” she said, describing a theme of the movie and of her husband’s life. ”Someone once called David a genius and he replied, ‘Yes, but it doesn’t come cheaply.’ ”

”Shine,” directed by Scott Hicks and released by Fine Line, has been embraced by audiences for its deft and often humorous depiction of artistic obsession and the crushing of a psyche. As a result, Mr. Helfgott’s concerts in Australia have become sellouts, and a recording of his music has climbed high on both classical and pop music charts in the United States and Britain.

He will soon embark on a 10-month tour of the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia. His schedule is still being completed, but he has concerts set for Symphony Hall in Boston on March 4, Avery Fisher Hall in New York on March 18 and the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles on March 25 and 27. When tickets to Mr. Helfgott’s first New York concert sold out in three days, he added a second concert at Avery Fisher on April 8.

The film is a remarkably faithful recounting of Mr. Helfgott’s life: his childhood of musical accomplishment and parental torment; his decade in mental institutions, away from music, and his halting return to the piano, first in a wine bar in his hometown of Perth, then, triumphantly, onstage again.

The portrayal of Mr. Helfgott by Mr. Rush, an Australian actor who is also a pianist — and who spent just five days with him — is uncannily accurate, with all its hyperkinetic warmth and self-aware humor.

”It’s the greatest movie ever made,” Mr. Helfgott exclaimed, delighted with the portrayal.

The crucial trauma of Mr. Helfgott’s youth seems to have occurred when his father, Peter, blocked an invitation from the violinist Isaac Stern for the boy to study music in the United States. When the teen-age David did leave at last to study at the Royal College of Music in London, his father disowned him.

Months later, after a successful performance of his father’s favorite piece, the demanding Piano Concerto No. 3 by Rachmaninoff, Mr. Helfgott suffered a mental breakdown that sent him into institutions. Doctors gave him electroshock therapy and for years forbade him to play the piano.

Mrs. Helfgott said she had a tape of her husband playing when he first returned to the instrument. ”The sadness and pain and wandering are dreadful to listen to,” she said.

At the piano for the recording session, Mr. Helfgott dipped gingerly into that sadness, touching on it quickly and skittering away as he practiced, over and over again, Chopin’s ”Raindrop” prelude.

”I’m lucky to be alive, lucky to be alive,” he said as his fingers moved over the keyboard. ”I’ve been through hell, been through hell, keep smiling, keep smiling, keep smiling. You have to remember I came from hell, I’m going to heaven. Dad’s in heaven, but he’s proud.”

What was his father like?

‘Well, my daddy was different from any other man in the world,” Mr. Helfgott said. ”Dad can’t help it, Dad can’t help it. He was demanding, but the point was, keep to the point, keep to the point, I should say that Dad was very demanding and cruel, cruel, cruel.”

Improbably, the movie has a happy ending as Mr. Helfgott begins to come to terms with the memory of his father and settles into a loving relationship with his wife, an astrologer 15 years his senior. Just as improbably, this story has another happy sequel, as he seems to be thriving on the publicity and fascination with his life that the film has produced.

In her book about their relationship, ”Love You to Bits and Pieces,” now being released by Penguin in the United States, Mrs. Helfgott describes her husband’s life in what he calls the ”heaven” of their rural home in Promised Land, two hours northwest of Sydney, where she said he plays the piano at least six hours a day.

His pleasures away from the piano include swimming in their large pool, and traffic jams, which, to the amusement of his wife and friends, he adores.

”I love traffic, I love traffic,” he said the other day as Mrs. Helfgott drove him to the recording session in this town 30 miles west of Sydney. ”Traffic is very important, and it shouldn’t be ignored,” he said. ”You have to be alert because there’s a pattern in the traffic and it helps you to concentrate and to relax. It’s very important to enjoy the journey.”

Mr. Helfgott remains on a medication called Seranace for a psychological disorder that doctors have found difficult to name. ”He is not schizophrenic or manic-depressive,” Mrs. Helfgott said. ”He is never depressed. He’s just a delightful eccentric.”

She said his dosage had been kept deliberately low to avoid muffling his creativity. ”If we gave him more, he could be easier to live with in certain ways, but you could turn him into a ghost of himself.”

To polish his playing and help keep him focused at the piano, Mr. Helfgott now meets regularly with a piano coach, Mikhail Solovei, who heads the department of piano at the Melba Conservatorium in Melbourne and lectures on piano at Monash University.

”I have never seen anything like this in my life,” said Mr. Solovei, who spent years as a concert pianist in Russia. ”After the movie, everyone wants to hear him, everyone wants to see him. It’s something enormous.”

The intimate mood of the movie seems to have created a sense of personal involvement in his audiences, Mrs. Helfgott said.

”Some people like to sit in the front row, and if they can catch some of what he says, they get quite excited,” she said. ”They feel as if they are sharing his inner thoughts, which of course they are.”

One listener recalled with delight a concert at which Mr. Helfgott paused briefly as he played, muttered, ”Here comes a hard part,” and plunged ahead.

For all his obvious pain and fragility, it is another rare quality that draws people to him: his childlike warmth and affection.

”Sometimes you want to eat him, he’s so cuddly,” Mrs. Helfgott said. ”You just want to snuggle up to him.”

Mr. Solovei agreed. ”He is absolutely lovable, though very fragile, that’s true,” the teacher said. ”His problem is that he reacts to everything, whatever he sees, whatever he feels. He has to hug everyone. He has to comment on everything. Sometimes he likes to hug the piano and kiss the piano.”

He added: ”I would say he is a happy character. Maybe not all the way down: maybe some way down is the tragedy. Sometimes for no reason, sometimes he can start crying. But it goes away very quickly. The happiness is not a fake. He really has this very charming personality.”

At the piano, Mr. Helfgott’s efforts at concentration are palpable and, sitting forward in their seats, his audiences join him in his struggle to stay focused.

”He mostly hears what he wants to hear, not always what is there,” Mr. Solovei said. ”His playing is mostly wonderful. His intentions are wonderful, but he just needs a little more control so that he produces what he is hearing in his head.”

Or, as Mrs. Helfgott puts it: ”Sometimes you’ve got to be a bit firm with him. Otherwise he just mucks about.”

Mr. Helfgott and Mr. Solovei are sitting side by side on the piano bench preparing for the final piece in today’s recording session, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. Mr. Helfgott has one arm around his teacher, and he is leaning his head on Mr. Solovei’s shoulder.

”Remember to pedal, David; don’t be lazy,” the teacher says. ”See? Pedal and pedal. Two in a row.”

”I’ll try, I’ll try,” Mr. Helfgott says. ”Pedal, pedal. I love pedal.” He begins to play, buzzing to himself.

”David, David, don’t fake the left hand! Play!” Mr. Solovei urges.

”Ksss, ksss, ksss.”

”Pedaling, pedaling, David,” Mr. Solovei says. ”Pedal.”

”Ksss, ksss, ksss.”

”Enjoy it more,” Mr. Solovei cries as the music takes flight. ”Smile! Smile!”

”Must be aware, got to be aware,” Mr. Helfgott says, well into the music now. ”I know why. Just smile, just smile. Never mind, never mind. I’m pretty good sometimes. I’m pretty good sometimes. I’ll play it if it kills me. Just keep smiling, just keep smiling. Better keep playing. Better keep playing.”

Copyright The New York Times