With Screwdrivers in Hand, a Magic Man Does Battle With the Spirits

LAU, Indonesia, August 27, 2001 : Where did that crab come from?

With a casual flourish, Sukari Yasir pulled his hand from under his patient’s gut and held up the crab, wet, whitish, wriggling slightly, about three inches long.

”It didn’t hurt when it went in, so it doesn’t hurt when it comes out,” said Mr. Sukari, 64, explaining why there was no exit wound.

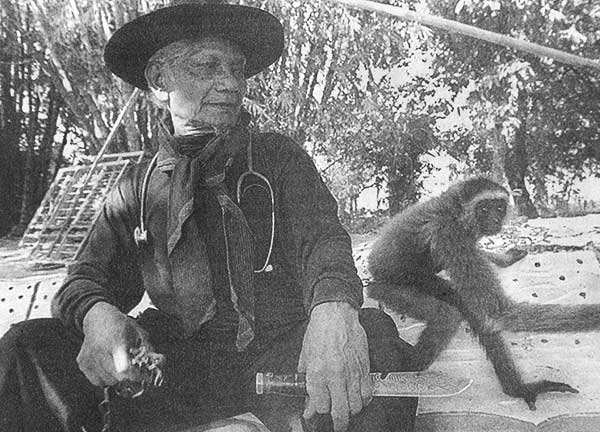

In his all-black outfit and black gaucho hat, his stethoscope around his neck and his medical tools in hand — a dagger and two Phillips screwdrivers — he seemed an unlikely medical man.

But he is pretty typical around here — a dukun, or faith healer, who performs white magic to extract the cursed objects that black magicians have inserted into people’s bodies to make them sick.

”This is a gift from God and I am just his instrument,” Mr. Sukari said as the crab crawled up his wrist. ”These are things that a doctor couldn’t find. I don’t make things up. I take animals out of people’s bodies.”

He poked at the back of another patient, one of eight who were sitting shirtless in the sun on a wooden bench. ”There’s something in there, feel it?” he said, and some of the people who tried said they could.

Mr. Sukari burrowed his hand beneath the man’s rib cage and came out with a handful of rubble: three pebbles, a small crystal and a rusty nail. With a flip of the hand he tossed them onto the ground.

A goat bleated nearby, and Mr. Sukari’s trained parrot called from its cage: ”Allah!”

”I didn’t feel anything,” said Masrian, a 45-year-old farmer who had been relieved of his crab. ”I was a little bit surprised.”

He said he had been sick for about two years with an ailment that bewildered medical doctors. ”Half of my head is always hurting and there’s a burning feeling in my nose,” he said. ”Also I have back problems.”

Another patient, Sukran, 60, said: ”I used to be crazy. I stopped people in the marketplace and threatened them with machetes. I’ve been coming here for a year now and I feel better as long as I don’t eat meat.”

Faith healers — some mixing mysticism with chicanery — are a common feature of rural Indonesia, said Ronny Nitibaskara, an anthropologist at the University of Indonesia.

Many, like Mr. Sukari, have studied for years, using fasting, prayers and training in traditional martial arts. People visit them for cures, to find missing property, to learn the future and to ward off evil. They pay what they can — some eggs, a chicken, a few thousand rupiah.

”People fear them and respect them,” Mr. Nitibaskara said. ”Their mistakes are excused and their word is accepted even though it is wrong and it is nonsense.”

Many people in Indonesia appear to be unsure what to believe and many take the position that it is safest not to rule anything out.

Almost everyone seems to have heard of mystics who can perform extraordinary feats, or to know someone who has witnessed them. One young man said he had a friend who had seen a mystic turn a peanut into a stone, though what the purpose might be was unclear.

Some faith healers say they can fly or disappear or are invulnerable to harm. Mr. Sukari was charmingly evasive when asked if he had such powers.

”They say that I can fly, do you believe it?” he said. ”A helicopter flies like me. It’s not that I can’t disappear, but if I do I might not come back.”

He did say, though, that when he rides on buses he is not always asked to pay a fare. ”Maybe it’s that they can’t see me,” he suggested.

He was less modest about his cures, selling his patients magic pills and giving them verses to memorize that he said would make them immune to bullets.

Mr. Sukari, an elfin man who cracks jokes even as he calls spirits from the vasty deep, said he trained for years in the arts of magic, learning to walk through fire, fasting at the bottom of a well and studying the dark secrets of his art.

He does not say where he learned the dextrous hand movements that allow him to produce from the torsos of his patients an assortment of crabs, frogs, bats and cockroaches as well as screws, hinges, seashells, chicken bones, twigs, nails — most anything a person might find as he walks along the road.

It is the ritual that makes it tempting to believe, along with Mr. Sukari’s friendly charm.

The cure begins with an evening session of prayer and diagnosis that precedes the morning surgery.

As his caged birds and monkeys call from the yard outside, his patients sit shirtless on the floor of a darkened room as he examines their backs, mumbling incantations as he does so.

He pokes with his fingers, slaps with the side of his dagger, scribbles on their skin with a ballpoint pen. He listens with his stethoscope and prods with his screwdrivers. One lights up with a small red light when he pushes a button. The other makes a beeping sound.

”Not much nutrition in the blood,” he said of one patient as his screwdriver beeped. And of another, ”Dirty blood, difficult to get the blood pressure.”

Then, moving from one patient to another, he dug his fingers into pressure points and the patients grimaced and twisted, some of them rising involuntarily to their knees.

The key diagnosis comes when the patient lies on his back and an egg is placed on his stomach. ”Instead of using an X-ray,” Mr. Sukari said, ”I use a chicken egg to find out what’s going on inside.”

And in any case, he said, these are not the kind of objects that an x-ray would detect. ”They are invisible to modern science.”

As for the malevolent crab, Mr. Sukari placed it in a small plastic bag filled with water. Giving the patient, Mr. Masrian, a special prayer to recite, he told him to return the crab gently to a pond.

Copyright The New York Times