The Wisdom of the Zippo Lighter, Tiny Missives from the Vietnam War

HO CHI MINH CITY, Vietnam, Dec. 7, 2006 : “Off the record,” Bradford Edwards said, though this seemed an odd thing to say when stating the obvious. “Off the record I’m a little obsessed with the Vietnam Zippo.”

He collects the metal lighters by the hundreds; he studies them; he celebrates them as tiny symbols. He searches for deeper meanings in the epigrams etched into their shiny sides by the American soldiers who left them behind. With grave whimsy he turns them into art.

For 10 years, starting in the early 1990s, he said, he bought them on the streets of Ho Chi Minh City, where they were sold as souvenirs until the supply of genuine wartime lighters ran out.

“I have handled thousands of them; I have handled maybe 10,000 of them,” he said. “I’m really deep into this. I’m saturated with it. But I still haven’t lost my belief in the significance of the Zippo.

Mr. Edwards, 52, is an American artist who spends much of his time in Hanoi creating art mostly from found objects and images. His father, Roy Jack Edwards, who died last year, was a fighter pilot over Vietnam, a distant, mythical figure to his son. The younger Mr. Edwards missed the war himself, and his obsession with Zippos obviously has to do with more than little silvery boxes used to light cigarettes.

“My dad was a super-professional soldier,” he said. “He was a serious cat who taught at the Naval Academy, worked in the Pentagon and taught weapons design. He was one of 100 Marine Corps pilots, and he did a couple of tours. I grew up with Vietnam in my life from Day One.”

If Vietnam and his warrior father remain enigmas to him, the answer, perhaps — if it is not blowing in the wind — can be found etched on the sides of Zippo lighters:

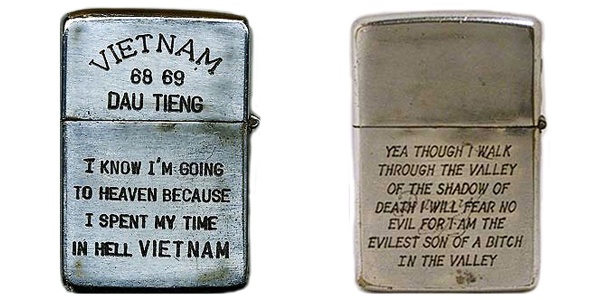

“Yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil for I am the evilest son of a bitch in the valley.”

“Death is my business and business has been good.”

“I’m not scared, just lonesome.”

“Please! Don’t tell me about Vietnam because I have been there.”

The Zippo is a humble, utilitarian object, a chrome-plated brass oblong 2.2 inches high and 2.05 ounces in weight that can be flipped open and lighted with one deft movement if you practice long enough and produces a gratifying thwink when snapped shut.

But in Vietnam, Zippos were more than lighters. Like miniature versions of the crests of medieval knights, they bore the mottos that defined what many soldiers understood, deep down, to be an absurd mission.

In a way they were akin to tattoos, and often the engraving was done at small roadside parlors.

“This is pure,” Mr. Edwards said. “Pure art without ambition, a real and honest venting of feelings: ‘We are the unwilling led by the unqualified doing the unnecessary for the ungrateful.’ ”

In his art Mr. Edwards has found more than 100 ways to present the Zippos, he said, using lacquer, mother-of-pearl, silk-screen printing, metal etching, stone carving, graphite drawing, silver leaf, photography, mixed media and more.

With the help of Vietnamese masters in these arts he has arranged Zippos in grids, created steel-plate poems with them, photographed mass layouts of them from two stories up, used them to build an oversize working abacus.

It all means something. “The Zippos were the witnesses,” he explained, “and I am simply the messenger.” He has shown his Zippo art in Oakland, Calif., where he lives, and in Vietnam. A glossy book of his work is being prepared for publication next year titled “Vietnam Zippo” (Asia Ink, London).

All this, he said, in the interest of “going deeper and deeper in pursuit of the meaning of the Zippo.”

That notion, so peculiar in its high seriousness, seems in itself to draw Mr. Edwards closer to the spirit of the men who poured their hearts out on the sides of lighters.

“Tragedy and pop, kitsch and irony,” Mr. Bradford said. “There’s a lot of raw emotions here. It’s not all tongue in cheek. Touching, sad, provocative, genuine expressions. There’s some strong juju here. Strong juju.”

“I know I’m going to heaven because I’ve spent my time in hell: Vietnam.”

“Ours is not to do or die, ours is to smoke and stay high.”

“You’ve never really lived until you’ve nearly died.”

“If you got this off my dead ass I hope it brings you the same luck it brought me.”

It is almost impossible any longer to find a genuine wartime lighter for sale here, Mr. Edwards said. What remains are fakes of varying sorts, including knockoffs made in China.

“That scene is over,” he said. “There are no real Zippos in Vietnam now.”

The Zippo Manufacturing Company in Bradford, Pa., says about 200,000 were used by American soldiers in Vietnam, though Mr. Edwards said he was convinced that the number was much higher. Most of those that were left behind were lost or given away, he said; it was rare for a lighter to be scavenged from the body of a soldier.

“They used them to provide light, to light candles, to burn a hut, to light a flame thrower,” Mr. Edwards said. “They were utilitarian, but they were very personal items.”

“They are powerful documents,” he added. “These documents are etched in metal. It’s not sterile, it’s not flighty, it’s not pen and paper. It’s etched in metal. The only thing closer to eternity is stone.”

And so, from all the thousands of Zippos he has handled, does this artist have a favorite? He does.

“I’m not someone who has a favorite movie or a favorite color or a favorite anything,” he said. “I’m not a favorite kind of guy. But I can tell you my favorite Zippo — the best Zippo, the one I would never sell, unless it was for maybe a thousand bucks.”

This Zippo carries on one side an official emblem, the military insignia of a riverboat with a skull and crossbones and the legend “Give no quarter.”

Turn it over, and four words have been etched into the chrome that seem to embrace the wisdom of all the other Zippos he has collected: “You can surf later.”

Riverboat duty was some of the most dangerous in the war, Mr. Edwards said, riverboats and helicopters. And how many surfers, really, ended up on Vietnam riverboats?

“This guy on the boat, we don’t know who he was,” he said. “We don’t know if he survived. But we’ve got this Zippo. I like it because it’s not enigmatic. It’s not ironic at all, it’s not tragic or sad. It has no deeper meaning.

“The only way he can get through this every day, the firefights. He gets his lighter, and he lights his joint, and he looks at his lighter and thinks to himself: ‘You can surf later. I’m going to get through this.’ ”

Copyright The New York Times