Stark Village Justice: Must the Lovers Be Flogged?

DHAKA, Bangladesh, June 15, 1987 : Disgraced and threatened with public whipping, the lovers have turned against each other, and their stories, told in sullen monotones, are now at odds.

But one thing is certain. Late one recent night, Abdul Jalil and his neighbor's young wife, Khurshida Ali, were caught as they tried to elope, shaming their families and their village of Bholail, which is about 10 miles south of Dhaka.

Now they faced the judgment of an ancient trial system known as salish, where village elders, mostly tradesmen and small landowners, would exact justice that could include a public whipping or slapping and a forced realignment of the marriages involved.

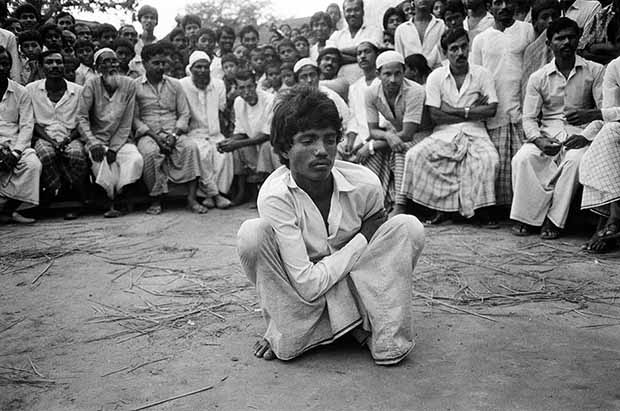

Abdul Jalil on trial. :

As the salish began, Mr. Jalil, a helper on a minibus who thinks his age is about 25, squatted at dusk in a small courtyard, surrounded by the men and boys of the village as the elders, smoking expensive imported cigarettes, discussed his crime.

''I hardly even know her,'' he said of Mrs. Ali. ''She tempted me into it. She made advances.''

The women, who play a secondary role in this Moslem society, were hidden in an adjacent building. Mrs. Ali, if her testimony was needed, was to speak into the courtyard through a darkened window.

The salish, increasingly rare in Bangladesh, represents an attempt by village leaders to maintain their traditional feudal control and to cling to age-old customs - such as the subordination of women - in a slowly modernizing nation.

It is an illustration of the distance that remains between thousands of isolated villages and the structures of government, which have yet to reach much of the country with paved roads, electricity, water and administrative control.

Recourse to the salish also demonstrates a local mistrust of the police, who are described as corrupt and abusive, and of the government court system, which villagers said is slow, complicated and alien to their customs.

''I am a poor man and I cannot afford to go to the police,'' said Tamizuddin, the father of Mr. Jalil's wife, Hamida.

''If we go to court we will be trapped in the system,'' said Mr. Tamizuddin, who is a farm laborer. ''The most powerful forces will win and there will be no justice.''

But like the courts of the distant cities, the salish snagged this night on a technicality when the aggrieved husband, a bicycle-rickshaw driver named Mohammad Suruj Ali, failed to appear.

Two nights later, the salish was again delayed when the accused himself refused to take part.

As a monsoon downpour brought a luminous early dusk to the village and green rice fields, the other principals gathered at the house of a village elder, a cosmetics salesman named Guyashuddin Ahmed, to discuss the case.

Standing almost unnoticed among them, in the shadows by a postered bed, was Mrs. Ali, a slight woman of 18 with delicate features, wearing a faded red-print sari.

A visitor asked for her side of the story.

''I ran away because my husband couldn't provide for me,'' said Mrs. Ali, the daughter of a subsistence farm laborer. ''I hardly even know the man.''

''My godmother persuaded me to do it,'' she said without expression. ''I didn't want to go. The boy talked me into it. He said he would take the responsibility. He took me by force. He beat his wife and blood was coming from her mouth and nose.''

Indeed, Mr. Jalil had recently received a warning from a session of the salish for having beaten his wife, and Mr. Tamizuddin had taken her away from him.

From behind a curtained doorway across the room came a woman's low voice: ''Don't believe her. She's a loose woman. She is lying.''

''I am not,'' said Mrs. Ali just as quietly. ''I had work in a garment factory.''

''She didn't work,'' said the voice from behind the curtain. ''She played around. She's a slut. Someone said, 'Come with me,' and she went.''

''It's not true,'' the young woman said, cracking her knuckles as she spoke. ''He forced me to go with him.''

''Don't believe her,'' said the voice. ''These are the stories she prepared for the salish.''

Subhan Sardir, a member of the salish, removed his glasses in a gesture that brought silence to the room.

''We may or we may not whip them,'' he said of the offending couple. ''But we will probably force them to marry.''

''Will you marry him?'' he said, turning on Mrs. Ali. ''You won't? You won't go?''

''I won't,'' she said.

''How will you eat, all alone in the world?'' he asked. ''Who will feed you?''

''I'll find some way,'' she said.

''You ran away with that boy and now you refuse to marry him,'' said Mr. Sardir, brandishing a large flashlight and raising his voice. ''You know me. I'll bet you never got a real whipping from your father. I'll show you what a real whipping is.''

He turned to the visitor. ''She'll accept,'' he said. ''She must accept. She has put the whole village to shame and it is our obligation under Islamic law to rectify that shame. We will force her to marry him, and force him to marry her.''

At that point Mrs. Ali's husband, the rickshaw driver, entered the room. A soft-spoken man of 25, he looked everywhere but at his wife.

''Will you take her back?'' Mr. Sardir asked him.

''No,'' said Mr. Ali quietly.

''I feel sorry for her,'' Mr. Sardir said. ''She's a very simple girl and she was deceived by fancy words. But we are doing what we must do.''

''She is a fallen woman now and nobody else will marry her,'' he said. ''It's the boy's responsibility now to take her as his wife and support her. Otherwise she will starve.''

Mrs. Ali remained standing in the shadow by the bedpost, one bare foot crossed slightly over the other.

When the salish convened again, the village elders tried to persuade the accused man and woman to get married but they declined.

Mr. Jalil and Mrs. Ali were flogged in public, he 30 times and she 20 times. Mr. Jalil was fined as well.

''I want my wife back,'' he told the salish. But his father-in law, Mr. Tamizuddin, said his daughter would never go back to such a man.

Mrs. Ali said, ''I'll work as a maid servant to fend for myself and will never marry again.''

Copyright The New York Times