Surviving the Killing Fields, then Ambushed by AIDS

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia, July 7, 2001 : Just as Cambodia is emerging from three decades of war and mass killings, it finds itself swept by the beginnings of a new scourge: AIDS. Cambodia is the sickest country in Asia now, at risk for a devastating spread of the disease.

In Cambodia’s cities and scattered villages, it is common now to see spectral figures looking much like the starving victims of the Khmer Rouge years. Two million people died when the Communist Khmer Rouge ruled the country from 1975 to 1979, and many more lost their lives in the civil war that followed.

One of these new sufferers is Touch Saroeun, a weak and wasted man of 31 with large, glowing eyes and the stunned look of someone who has been ambushed.

When he was a Khmer Rouge soldier not long ago, he was certain that nothing could kill him. His comrades marveled, he said, as he strolled through a minefield to buy a pack of cigarettes.

As a tank driver — shackled to his tank like the others so he would not flee he survived some of the fiercest battles in more than a decade of civil war.

Peace came three years ago, and it is peace that has brought him death.

Touch Saroeun :

When the war ended, the minefields around the former Khmer Rouge stronghold at Pailin were cleared away. At the same time, brothels opened, bringing women more beautiful than any he had ever seen. ”I was so excited that I got drunk and forgot to wear a condom,” Mr. Touch Saroeun said.

When he fell ill, he said, he discovered that half the men at the hospital in nearby Battambang, mostly soldiers, were infected like him, with H.I.V., the virus that causes AIDS. And when he transferred to a hospital here in the capital, he found its courtyards and corridors populated with AIDS patients.

Around the country about 170,000 people are believed to be infected, nearly 3 percent of the adult population. This number is still far lower than the 36 million infected in Africa, where the epidemic is well entrenched, or in the United States, where more than one million have been infected and 450,000 have died.

”In my more pessimistic moments, I’m afraid that in the next few years more people could die of AIDS than in the Pol Pot time,” said the Rev. James Noonan, a Maryknoll priest who administers the Seedling of Hope H.I.V./AIDS Project.

That may be an exaggerated fear, but in the dark heart of the epidemic it is not uncommon for the sufferers themselves to make the comparison. The biographies of patients invariably include past horrors.

”Now I am suffering just like in the Khmer Rouge time,” said Ngau Rotheany, 39, a patient at Calmette Hospital in Phnom Penh whose husband has already died of AIDS. ”No husband, no money, nothing to eat, sick and suffering.”

Experts see a pale ray of hope that Cambodia may avoid the worst. United Nations specialists are finding signs that awareness of the illness and its causes has been rising, along with increased use of condoms. The infection rate among young sex workers appears to be dropping.

The very sight of the emaciated victims may have done more to advertise the scourge than any amount of public education. Almost everyone in Phnom Penh seems to know someone who is infected.

People who work with patients here say they are wary of optimistic predictions.

”What we see every day is that the number of people developing AIDS and dying is very high and it’s not declining at all,” said Catherine Quillet, the chief of the French mission of Médecins Sans Frontières. ”We have more and more patients arriving and fewer places where they can go.”

Particularly tragic is the high cost of treatment, she said. Desperate patients and their families sell their motorbikes, their farm animals and even their land to pay for ineffective herbal potions or for sophisticated Western treatments that they cannot afford to continue.

The patients die and their families are left destitute.

Perhaps even more painful is the stigma that causes many sufferers to be abandoned by their families and shunned by their neighbors.

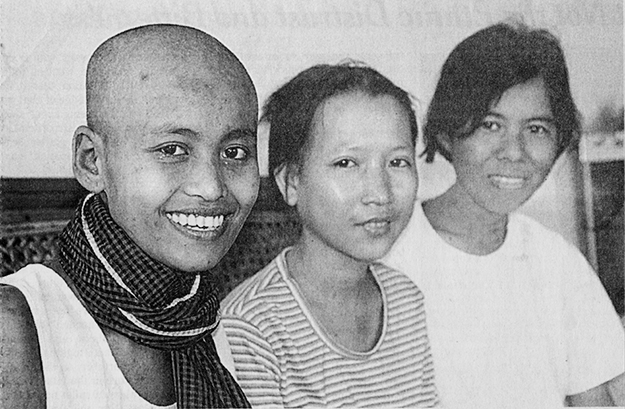

Keo Chantha (left) with fellow AIDS patients.

Before forcing her to leave their home, the relatives of Mrs. Ngau Rotheany made her sleep in an outhouse, cook on a separate fire and eat off a separate plate. They ordered their children to stay away from her, telling them, ”Why do you want to talk to someone with AIDS?”

Vieng Chantha, 33, who was also infected by her husband, gave away her three children when she fell ill. Her family rejected her with the words, ”Go somewhere else to die.”

At the Maryknoll hospice in southern Phnom Penh, where 12 patients wait out their days shivering and coughing under their blankets, Keo Chantha, 23, is familiar with abandonment. She was sold into prostitution by her brother at the age of 14.

Bald now and scratching at her scabs, she has nothing left of her former beauty but her radiant smile.

She said she had one wish now, to see her mother before she dies. She sent a friend to her village to beg her parents to visit, but they refused.

Uy Kimheng, 33, looked down at her hands and clipped her nails as she described her ailments — weakness, loss of appetite, tuberculosis. In her bright yellow T-shirt, she looks too healthy to be waiting for death.

With a shy smile, she admitted to feeling angry: at the Khmer Rouge who killed her father, at the husband who infected her.

The hardest thing now, she said, is that she cannot sleep at night. ”I wake up at 4 in the morning and I lie there thinking,” she said.

Thinking about what?

She smiled again in embarrassment. ”I think about the day I’ll die.”

Mr. Touch Saroeun, the former Khmer Rouge soldier, is luckier. His father, a subsistence farmer, has visited him in the hospital in Phnom Penh and plans to take him home to his distant village to care for him.

But Mr. Touch Saroeun said it was terrible to have to tell his father that he was sick. ”My father loves me very much,” he said.

When the old man came to visit, he sat quietly beside his son on his bed, caressing his hand.

”I told him I was sorry,” Mr. Touch Saroeun said. ”He was so sad and he kept looking into my face. He didn’t say anything. He just looked at me and shook his head.”

When Mr. Touch Saroeun leaves for his village, the hospital will give him a month’s medicine to treat his symptoms. He will have the right to return each month for more, he said, but he does not know where he will get the money to make the trip.

Copyright The New York Times