1988 : Mass uprising in Burma

RANGOON, Burma, Aug. 8, 1988 — A surge of military violence that has swept Burma and shaken its Government began at exactly 11:30 Monday night, when the brightly lit golden spire of the Sule Pagoda vibrated with the rumble of an approaching tank.

Throughout the day, 10,000 angry but unarmed protesters had confronted helmeted soldiers with fixed bayonets, and the soldiers had fallen back, issuing periodic ''last warnings'' over a loudspeaker.

The tanks roared at top speed past the pagoda, followed by armored cars and 24 truckloads of soldiers. The protesters scattered screaming into alleys and doorways, stumbling over open gutters, crouching by walls and then, in a new wave of panic, running again.

As the first 15-second volley of gunfire echoed through the dark square, the students who led the protests still stood by their red banners, facing down the soldiers

Hospitals reported four people killed in the first shooting, their ages ranging from 13 to 16. Twenty-two people were reported seriously wounded.

Since the incident at the Sule Pagoda, nearly 100 people have been killed by soldiers, according to the official count. Far greater numbers have died in repeated military volleys, according to unofficial tallies from around the country, as the

spontaneous and mostly nonviolent protests against the military-dominated Government that has ruled Burma for 26 years have spread and intensified.

In dozens of interviews on the streets of the capital over the last four days, anti-Government sentiment appears to be universal as people abandoned their fear of the repressive regime and voiced a long-suppressed anger.

Despite its overwhelming superiority of force, the regime is today under siege by its people. The protests, which have spread to every major city since they began on Monday, have been led by students and joined by large numbers of workers and Buddhist monks, as well as by a cross-section of citizens, including Government employees.

''No one likes this brutal Government,'' said the owner of a curry shop. ''It has no respect for the people, no respect for human rights. All the people are angry now. All the people support the students.''

The protests have brought the capital to a virtual standstill, with marketplaces nearly deserted, shops closed and dock and transport workers on strike.

An early morning drive today found weary soldiers taking up their positions and residents, sometimes less than a block away, tending to homemade barricades against the patrolling troops.

These mostly symbolic barriers now crisscross the city's tree-shaded streets, flimsy jumbles of paving stones, tree branches, bits of fencing and even refuse, and sometimes topped by uprooted stop signs.

The protesters at the barriers, peering into the distance for the approach of the army, scatter in panic as troop convoys led by tiny armored cars cruise past on what amount to urban search-and-destroy missions.

Dodging the convoys, fast-moving groups of masked protesters march with red flags through the sometimes rainy streets, joined for a few blocks in each neighborhood by residents who take up their anti-Government chants.

''Doh ayei! Doh ayei!'' they chanted, a phrase meaning roughly, ''It is our task,'' and symbolizing the people's determination to reclaim their country's affairs after the authoritarian one-party rule of the former national leader, U Ne Win. He resigned his post in late July, citing earlier anti-Government protests, and was replaced by U Sein Lwin, a hard-liner who reportedly commanded the forces that suppressed riots in March.

In an instant of particular brutality, one group of marchers was caught and chased into the grounds of Rangoon's General Hospital on Wednesday by several truckloads of soldiers.

According to several witnesses, two doctors and three nurses were killed and two nurses wounded when the soldiers opened fire on them as they pleaded for the lives of the marchers.

A pent-up fury at the Government, which has brought this potentially rich country to economic ruin, has been ignited by the protests and the killings. However the current uprising ends, opposition to the regime seems to have taken deep roots.

''Happy New Year!'' a young man shouted, spotting a foreigner. ''This is our revolution day!''

But the protest appeared to have no clear leadership, and as long as the Government continued to act to crush demonstrations by force, there was no clear scenario under which the demonstrators could achieve their goal of bringing down the regime.

Diplomats here were watching closely for signs of a split in the armed forces or a crumbling of discipline in the army, which had prided itself on the fact that it was the police - not the armed forces - that had fired at protesters in the past.

Unconfirmed reports have spread that local commanders outside Rangoon have ordered their troops not to shoot, or even that soldiers have joined the students. But there was still no sign in the capital that military discipline had weakened.

In the absence of high-level contact with the secretive Government, diplomats could only speculate over the events of the last month, during which Mr. Ne Win in stepping aside was rebuffed by his hand-picked Parliament on his public call for a referendum on one-party rule.

After he was replaced by Mr. Sein Lwin, a former general widely reviled by the protesters, homemade postcards showing the head of Mr. Sein Lwin with the body of a dog have circulated among the protesters.

The diplomats speculated that events might evolve under which Mr. Ne Win could take power again, but such a move would not seem likely to satisfy the demonstrators. Despite his departure, they continued to chant, ''Down with the Ne Win Government!''

The cry on the streets is for democracy, a word that for many people seems to mean an improvement in the drab and harsh conditions of their lives. Burma, in fact, had a multiparty parliamentary democracy when Mr. Ne Win, then commander of the armed forces, staged his coup in March 1962.

Since the beginning of this year, the price of one pyi of rice - an amount the size of eight cans of condensed milk - has risen from 3 to 16 kyat. The Government this week raised the minimum wage to 8.05 kyats a day, or just over 20 cents at the black market exchange rate.

Some students circulated a set of demands to diplomats, although it was not clear if they had delivered these to anyone in the Government.

The demands included the removal of Mr. Sein Lwin and the holding of the multiparty referendum, an end to martial law and military brutality, the release of imprisoned students and critics of the Government and a reduction in the cost of living.

It was this last demand, diplomats said, that seemed to go to the heart of the matter.

The protests, the largest since Mr. Ne Win took power in the military coup, appear to have gone beyond anything the Government expected. They have persisted despite a lack of organization or resources.

In the last two days the peaceful protests, in which people defied ranks of soldiers carrying fixed bayonets, have taken an aggressive turn. Residents said one military truck was set afire in the melee at the hospital.

On Wednesday, the official Burmese radio reported attacks on police stations outside the city and the burning of buses and buildings.

Protesters in the northern suburb of Okkalapa, where bloody confrontations have continued for three days, were said to have seized a gun from policemen, stormed their outpost and shot dead one officer.

The radio reported that three policemen had been beheaded by crowds in Okkalapa and another town.

Diplomats said as many as 50 people were killed in Okkalapa on Tuesday and 200 wounded, half of them seriously, and fighting continued there today. [ The Rangoon radio reported that 17 more people had been killed, some of them in the small Okkalapa suburb. It also announced that the air force had dropped leaflets on Okkalapa warning people that they would be bombed if they continued to hold out behind barricades. ] Frustrated by the one-sided confrontation, young men have begun to roam the streets of Rangoon smashing such symbols of government as stoplights, telephone exchange boxes and buses.

''The army is like the enemy here in an enemy country,'' the owner of a small bakery said. ''They are not our countrymen. They are beasts without minds.''

On Merchant Street, a resident said, a small group of soldiers tried a conciliatory approach, asking people to help them remove a tree that had been felled to block the road.

The residents said an army major told them: ''Please help us. We are your friends, and we do not want to hurt you.'' But nobody moved.

The new protests began on Monday, the eighth day of the eighth month of 1988, a date, according to Burmese, when astrologers had predicted bloodshed leading to a collapse in government.

For several days, students as young as 12 years old had agitated at factories, telling workers, according to one account: ''You should dress like women. Why is it only the children who are out in the streets?''

At the Rangoon Port Corporation, according to this account, stevedores went on strike Monday morning demanding a raise in their monthly wage of 400 kyat, or $10 at the black-market exchange rate, which is nearly seven times the official rate.

''We just locked the doors, closed the shutters and sat tight,'' said an official at the port, which like most agencies in this centralized economy is run mainly by retired military men.

Military deployment was heavy Monday morning, with troops wearing the red, blue, green or violet scarves of their units standing with their fingers on their triggers at street corners and Government buildings.

Hundreds of policemen guarded the giant golden Shwedagon Pagoda, armed but barefoot in respect to the Buddhist shrine.

By mid-morning the first reports of protests reached foreign embassies: 300 students rallying at a soccer stadium, a small demonstration at the port joined by Government workers, crowds gathering by the textile mills.

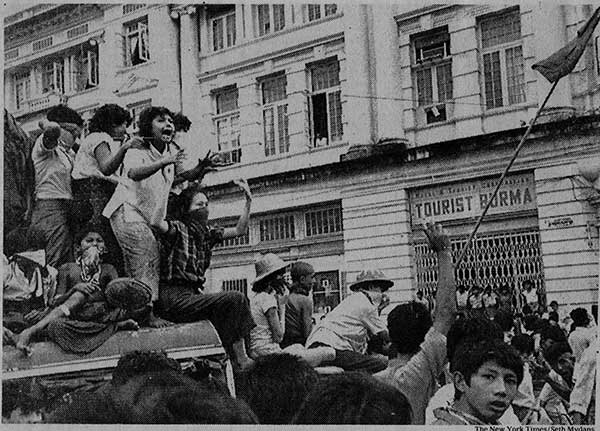

Soon huge crowds began moving toward the Sule Pagoda in downtown Rangoon, led by students with strips of cloth tied across the bridges of their noses.

The soldiers stood by impassively as the crowds surged past them, led by agitators urging onlookers to applaud.

People tossed cheroots and bananas to the leaders, and as the students passed they left banana peels in their wake.

''Everyone is tired of this Government, of this dictatorship,'' said an English teacher watching near the Ministry of Trade, which was guarded by a navy contingent.

''We are demonstrating to bring down this Government,'' he said. ''This Government has made us all beggars, and we do not want to be beggars.''

Soon afterward, when a military truck arrived and the troops climbed aboard to leave, the crowd applauded their departure, and the young soldiers broke into grins, one of them raising his blue peaked cap.

But by nightfall that mood had disappeared. After the killings at the Sule Pagoda, the shooting continued long into the night as soldiers chased down groups of protesters who marched, chanting slogans, through the isolated, tree-lined roads of the city's outskirts.

Elsewhere in the country protests were also under way. In Mandalay there were unofficial reports of two to four people killed. In Pegu, tens of thousands of people were said to have protested the killing of a monk. Protests were also reported in Moulmein, on the southern coast, and in several other cities.

Early Tuesday morning, students were marching again, and diplomats driving to their embassies saw shootings near the Shwedagon Pagoda that left more than a dozen bodies on the ground.

Shootings were reported at two high schools, with more students said to have been killed in each incident.

At the corner of 33d and Anawrahta Streets in the capital, demonstrators erected a small makeshift shrine to a student who had been killed there.

In some cases the students recovered the bodies, a number of which were said to have been shot in the head, and paraded with them on the tops of commandeered pickup trucks.

Diplomats received reports from military sources that the army's orders were now to shoot to kill.

Violence also spread outside the capital, and the Burmese radio reported that 31 people had been killed in the town of Sagaing.

On Wednesday the Government took its first public steps to address the protest, but their effect was lost in the continuing violence.

The authorities imposed a curfew of 8 P.M. to 4 A.M. and banned gatherings of more than five people, closed high schools and announced small raises in Government salaries. [ On Thursday the first statements by Government and military officials since the violence began were read on the state radio. They urged that the protests be made in a peaceful manner and promised to address the people's grievances ''insofar as possible.'' But they stopped short of announcing any substantive steps. ]

The capital was in a state of tension today, with residents standing in the streets waiting for the one-sided battle to move their way.

Most shops were closed, but street hawkers, unable to sacrifice a day's earnings, filled the sidewalks selling guavas, corn fritters, betel nut, fish soup and lottery tickets, reading palms and dispensing traditional medicine.

After 26 years of isolation from the world, few young people speak English, and the older men, struggling to express themselves, searched urgently for long-forgotten words.

''Tell the world,'' they repeated again and again as they saw their nation sliding into chaos, cut off from its neighbors.

''I wish any nation to interfere to save our country,'' said a maritime job recruiter. ''We want to be like other nations, to trade with other nations, to join the other people in the world.''

But with few foreigners in this dignified but crumbling city to witness their trouble, the painful sense of national isolation was palpable.

''You go back to your hotel. It is not safe here,'' one man told a foreigner. ''I will stay. I am a Burmese.''

Photos of protesters in Rangoon, Burma (NYT/Seth Mydans); Burmese troops (pg. A2) (AP); map of Burma showing location of Rangoon (pg. A2) (NYT)

Copyright The New York Times