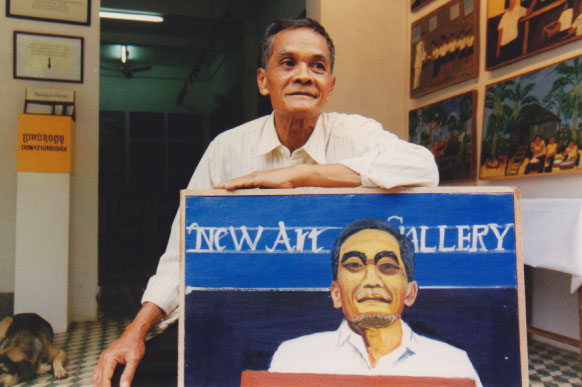

An Artist Preserving Life’s Little Moments

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia, July 2, 2001 : So far, there have been 128 events in Svay Ken’s life, almost all of them unremarkable.

He shined shoes at a hotel. He carried suitcases. He got married. He labored under the Khmer Rouge. He returned to the hotel. He sent his children to school. He mourned his wife when she died.

And one other thing. At the age of 60, nine years ago, he decided to paint pictures. He needed money, he said, and so ”one day I just started painting.”

He showed his pictures to the foreigners at the hotel. ”Some of the foreigners liked my paintings, some not,” he said in an interview. ”But the people who worked with me at the hotel, they said, ‘These are terrible.’ ”

Unschooled, naïve, prosaic, there seemed little of art in his pictures. But they were oddly charming, surprisingly magnetic. People began to buy them.

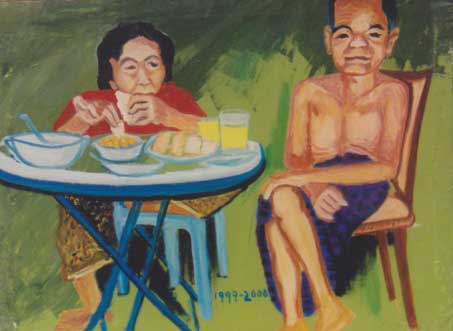

And then last year another unusual thing happened. When his wife, Tith Yun, fell ill and died, Mr. Svay Ken found himself in the grip of a new compulsion. He had to tell her story — his story.

”Tith Yun was born on Nov. 7, 1941, in the year of the snake,” he wrote. ”Tith Yun became my wife, and it is in memory of her that I write this account of her life and the family that we made together.”

There are millions of stories just like his in Cambodia, ordinary lives with a bloody gash in the middle from 1975 to 1979. That was when the Communist Khmer Rouge ruled the country, causing the deaths of two million people.

But this is a silent land where few people talk about the past. Like Mr. Svay Ken, most see themselves as ordinary and unimportant and their sufferings as too common to be noted. They prefer to bury their pain.

Mr. Svay Ken said he has no idea what made him different, what drove him to record his life, in words and then in an extraordinary series of paintings.

”After my wife died, I came out of the hospital, and I didn’t feel good,” he said. ”I just kept on thinking about my life. It was bothering me. So I wrote it down. I wrote to make it easy in my head.”

When they read his story, Ly Daravuth and Ingrid Muan, directors of the small Reyum Gallery here, urged him to tell it again in pictures. It took him a year.

The pictures in oils are on display now at the gallery — 128 of them — as straightforward and ingenuous as the artist himself.

”There is an immediacy to them,” Ms. Muan said. ”He didn’t take months to think about each picture. They are like instant pictures from his memories.”

There has been no description quite like this of what it has been like to live through the past half-century of upheaval in Cambodia.

Apart from several accounts by overseas Cambodians, there is almost no indigenous literature of the country’s tumultuous recent past. And the accounts that do exist focus almost entirely on the sharp edges of history.

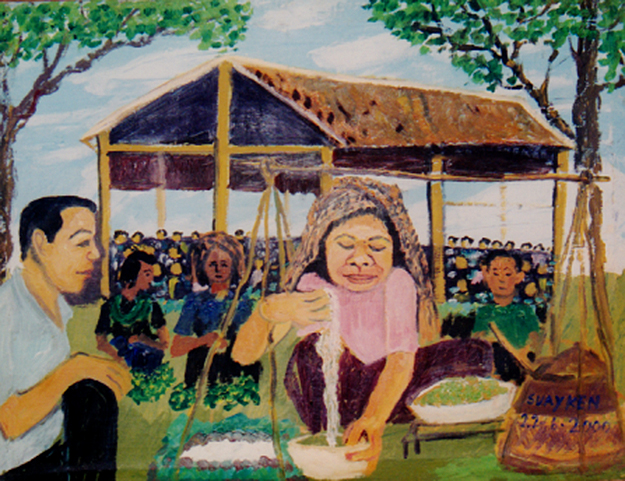

Mr. Svay Ken is a poet of the mundane, of the small moments that make up a life, no matter how big the history that surrounds them. Even his descriptions of the Khmer Rouge years focus on cooking, finding shelter and caring for his children.

Running in fear through the streets of Phnom Penh as the Khmer Rouge soldiers entered the city, he stopped for a glass of water — and stops in his painted narrative to record the moment.

”It’s interesting that the mundane parts of his life take up more space than the Khmer Rouge years,” Mr. Ly Daravuth said. ”There’s a before and an after. In his pictures, going to buy plates after he was married is as important as the Khmer Rouge time.”

Buying Dishes

And once it has been memorialized, each of these moments is as precious as a pebble plucked from a beach, polished, handled, examined and treasured.

”We went to buy plates for our new household at a store south of the New Market in Phnom Penh,” reads the title of one picture.

Next comes, ”Tith Yun carried her basket and scale to Doeum Kor Market,” followed by, ”We awoke at 2 in the morning to steam sticky rice cakes,” then, ”Tith Yun carried the steamed rice cakes to sell at O’Russey Market while I prepared the children for school,” and, ”Tith Yun sold her rice cakes alongside other vendors in front of the market.”

The snapshots of his life continue in measured order as Cambodia slides into the grip of war.

”Rockets fell in the city almost every day and every night,” and, ”At that time, the price of food rose very high. We couldn’t afford to buy Khmer rice, and so we ate only coarse-grained rice provided by United States donations,” and, ”Tith Yun asked me if she could go to sell silk in Ream.”

In the interview, Mr. Svay Ken insisted that there was no moral to the story of his life. ”I just sat and followed the flow,” he said. ”I wanted to show my life. I wanted to show it as a life of struggle, and that I made it through.”

But a mystery remains at the core of his story: his compulsion to remember and record and to turn his life into art. Although he is supported by his grown sons now, he said, he cannot seem to stop painting.

”I don’t need to work,” he said, ”but my hand won’t keep still.”

His hand was busy throughout the interview in his small home, where stacked paintings compete for space with cooking pots and a large crib. As his visitor scribbled his words in a notebook, Mr. Svay Ken scribbled too, in a notebook of his own.

Why?

”I can’t keep it all in my head,” he said. ”I take notes so I can remember.”

Copyright The New York Times