The President’s a Jailbird, in a Most Unusual Nest

MANILA, the Philippines, Dec. 28, 2001 : At least somebody takes his laundry home to wash and iron.

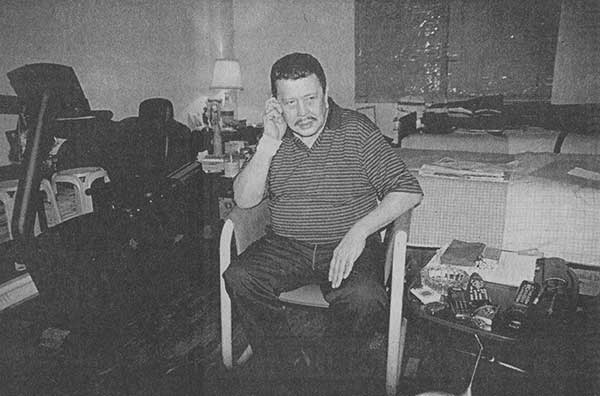

Neatly folded, his clothes are stuffed into three unzipped suitcases at the back of his gloomy little bedroom. Boxes and bags and shoes and jars of nuts and stacks of newspapers crowd the floor. Armed guards are posted in the corridor outside.

Previous address: Malacanang Palace.

Joseph Estrada, the first person — as he likes to remind a visitor — to serve as mayor, senator, vice president and president, is also the first former president to land in jail.

He twists a plastic rod to close the blinds as evening sets in.

”Oh, very lonely and depressing,” he says, coughing a smoker’s cough.

His jail is a threadbare suite in a veterans’ hospital, where he was transferred from a cell last summer when he pleaded ill health. Many Filipinos objected, saying their former president was being coddled.

Indeed, a secretary and a maid attend to him and his meals are brought from home. He has cluttered his suite with a treadmill, an exercise bicycle and three television sets. Several cellphones chirp a medley of jaunty tunes and he answers them, ”Hey, pal!”

There is plenty of righteous indignation to go around here in the Philippines, but no really coherent explanation for the harshness with which the country turned against its president.

His televised impeachment trial for corruption a year ago was blood sport: the Philippines versus its president. When it became clear in January that he would wriggle free, huge, angry crowds massed in the streets to demand his ouster.

Caught up in the moment, the Supreme Court declared his presidency null and void after just 31 months of a six-year term, citing what it called ”the will of the people.” The armed forces chief of staff took the cue and ushered him from the palace. He was replaced by his vice president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

”Actually my chief of staff committed treason because I was the constitutionally elected president,” Mr. Estrada said. ”And this is to be erased by more or less 400,000 people in the street. There is no more rule of law in the Philippines.”

It didn’t stop there. Having performed a constitutional Irish jig, the government turned the legal system loose on the ousted president.

In a country swarming with corrupt officials, Mr. Estrada became something of the fall guy. Accused of stealing nearly $80 million while in office, he is charged now with graft, perjury and illegal use of an alias as well as with a capital offense called plunder.

He may have been a bad president, but that bad? Perhaps Mr. Estrada has it right: it was a class thing. ”The so-called intellectuals and the rich are against me,” he said.

He didn’t behave like a president and he didn’t look like a president — slouching, shambling, overweight, his large head sagging with its dyed-black pencil moustache, looking more like a gangster than a statesman.

He was a drinker, a gambler and a carouser, and he flaunted it. ”I’m not hiding anything,” he said. ”I have a wife and two mistresses; about two.”

He was an affront to the sense of dignity of the country’s elite.

Even his corruption, which he denies, was embarrassingly inept and easy to track: suitcases of cash, forged checks. Former President Ferdinand E. Marcos, who was driven from office in 1986 and died in luxurious exile in Hawaii, managed to hide billions; a world-class thief.

Up close, though, Mr. Estrada is impossible not to like — open, vulnerable, without pretension of any kind, ready to accept any visitor as a pal. He seems to be without malice and his self-defense lacks bite.

”Cruel,” he said forlornly, describing his treatment.

His story illustrates one of the nation’s core problems. The Philippines is overwhelmingly a land of poor people governed by an entrenched elite.

This social divide was highlighted as never before when Mr. Estrada won office in 1998 by the largest margin of any president in history. He was elected by the poor, in defiance of the wishes of their betters.

The poor voters loved him for the persona he had perfected as a movie star, before entering politics — a common man ready to stand up for what is right against a selfish and abusive establishment.

He played that role, and still plays it, for all it is worth.

”I want my image to remain that way — macho,” he said, lighting a Lucky Strike. ”When you are above 60, I want to be remembered as I left, as a leading man, macho.”

Shortly after he took office, he said, a group of wealthy businessmen invited him to a banquet. After coffee was served, he asked to meet the kitchen staff. ”I want to shake hands with some people who actually voted for me,” he said.

He wasn’t really a man of the masses, though that seems to be where he belonged, with his lack of polish and his fractured English. Born into a middle-class family, he was the only one of seven siblings not to finish college — the only one not to become a lawyer or doctor or pharmacist or accountant. Even as president he seemed to be the black sheep.

If Mr. Estrada’s presidency was a flop, his trial since his arrest in April has been tangled in legal frippery and personal feuds.

It ground to a halt this month because of the suspension of two squabbling judges. Now one of the lead prosecutors has come under investigation for corruption himself.

An optimist has scheduled the next court session for early January. But to Mr. Estrada the case is a sham; at first he appeared in court unshaven and wearing slippers and refused to speak.

Now in his hospital room, sitting in his sweat pants and striped polo shirt, he fumbled for another cigarette and spoke over the sound of a televised soap opera.

”I still consider myself the legal, constitutionally elected president,” he said. ”I have not resigned. I am not incapacitated.”

His term of office still has more than two years to run.

Copyright The New York Times