The Hard Man of Singapore Knows the End is Near

SINGAPORE, Sept. 10, 2010 : “So, when is the last leaf falling?” asked Lee Kuan Yew, the man who made Singapore in his own stern and unsentimental image, nearing his 87th birthday and contemplating age, infirmity and loss.

“I can feel the gradual decline of energy and vitality,” said Mr. Lee, whose “Singapore model” of economic growth and tight social control made him one of the most influential political figures of Asia. “And I mean generally, every year, when you know you are not on the same level as last year. But that’s life.”

In a long, unusually reflective interview last week, he talked about the aches and pains of age and the solace of meditation, about his struggle to build a thriving nation on this resource-poor island, and his concern that the next generation might take his achievements for granted and let them slip away.

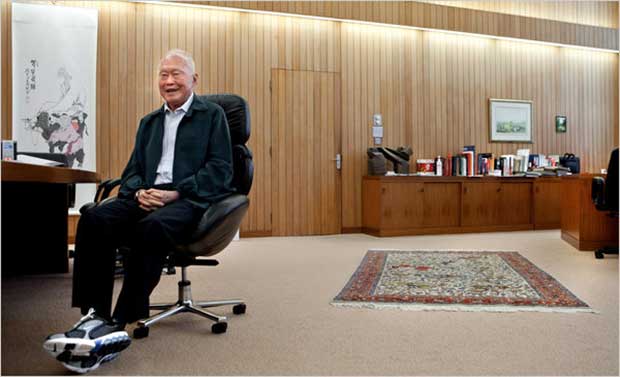

He was dressed informally in a windbreaker and running shoes in his big, bright office, still sharp of mind but visibly older and a little stooped, no longer in day-to-day control but, for as long as he lives, the dominant figure of the nation he created.

But in these final years, he said, his life has been darkened by the illness of his wife and companion of 61 years, bedridden and mute after a series of strokes

“I try to busy myself,” he said, “but from time to time in idle moments, my mind goes back to the happy days we were up and about together.” Agnostic and pragmatic in his approach to life, he spoke with something like envy of people who find strength and solace in religion. “How do I comfort myself?” he asked. “Well, I say, ‘Life is just like that.’ ”

“What is next, I do not know,” he said. “Nobody has ever come back.”

The prime minister of Singapore from its founding in 1965 until he stepped aside in 1990, Mr. Lee built what he called “a first-world oasis in a third-world region” — praised for the efficiency and incorruptibility of his rule but accused by human rights groups of limiting political freedoms and intimidating opponents through libel suits.

His title now is minister mentor, a powerful presence within the current government led by his son, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. The question that hovers over Singapore today is how long and in what form his model may endure once he is gone.

Always physically vigorous, Mr. Lee combats the decline of age with a regimen of swimming, cycling and massage and, perhaps more important, an hour-by-hour daily schedule of meetings, speeches and conferences both in Singapore and overseas. “I know if I rest, I’ll slide downhill fast,” he said. When, after an hour, talk shifted from introspection to geopolitics, the years seemed to slip away and he grew vigorous and forceful, his worldview still wide ranging, detailed and commanding.

And yet, he said, he sometimes takes an oblique look at these struggles against age and sees what he calls “the absurdity of it.”

“I’m reaching 87, trying to keep fit, presenting a vigorous figure, and it’s an effort, and is it worth the effort?” he said. “I laugh at myself trying to keep a bold front. It’s become my habit. I just carry on.”

HIS most difficult moments come at the end of each day, he said, as he sits by the bedside of his wife, Kwa Geok Choo, 89, who has been unable to move or speak for more than two years. She had been by his side, a confidante and counselor, since they were law students in London.

“She understands when I talk to her, which I do every night,” he said. “She keeps awake for me; I tell her about my day’s work, read her favorite poems.” He opened a big spreadsheet to show his reading list, books by Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling and Lewis Carroll as well as the sonnets of Shakespeare.

Lately, he said, he had been looking at Christian marriage vows and was drawn to the words: “To love, to hold and to cherish, in sickness and in health, for better or for worse till death do us part.”

“I told her, ‘I would try and keep you company for as long as I can.’ That’s life. She understood.” But he also said: “I’m not sure who’s going first, whether she or me.”

At night, hearing the sounds of his wife’s discomfort in the next room, he said, he calms himself with 20 minutes of meditation, reciting a mantra he was taught by a Christian friend: “Ma-Ra-Na-Tha.”

The phrase, which is Aramaic, comes at the end of St. Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, and can be translated in several ways. Mr. Lee said that he was told it means “Come to me, O Lord Jesus,” and that although he is not a believer, he finds the sounds soothing.

“The problem is to keep the monkey mind from running off into all kinds of thoughts,” he said. “A certain tranquillity settles over you. The day’s pressures and worries are pushed out. Then there’s less problem sleeping.”

He brushed aside the words of a prominent Singaporean writer and social critic, Catherine Lim, who described him as having “an authoritarian, no-nonsense manner that has little use for sentiment.”

“She’s a novelist!” he cried. “Therefore, she simplifies a person’s character,” making what he called a “graphic caricature of me.” “But is anybody that simple or simplistic?”

The stress of his wife’s illness is constant, he said, harder on him than stresses he faced for years in the political arena. But repeatedly, in looking back over his life, he returns to his moment of greatest anguish, the expulsion of Singapore from Malaysia in 1965, when he wept in public.

That trauma presented him with the challenge that has defined his life, the creation and development of a stable and prosperous nation, always on guard against conflict within its mixed population of Chinese, Malays and Indians.

“We don’t have the ingredients of a nation, the elementary factors,” he said three years ago in an interview with the International Herald Tribune, “a homogeneous population, common language, common culture and common destiny.”

Younger people worry him, with their demands for more political openness and a free exchange of ideas, secure in their well-being in modern Singapore. “They have come to believe that this is a natural state of affairs, and they can take liberties with it,” he said. “They think you can put it on auto-pilot. I know that is never so.”

The kind of open political combat they demand would inevitably open the door to race-based politics, he said, and “our society will be ripped apart.”

A political street fighter, by his own account, he has often taken on his opponents through ruinous libel suits.

He defended the suits as necessary to protect his good name, and he dismissed criticisms by Western reporters who “hop in and hop out” of Singapore as “absolute rubbish.”

In any case, it is not these reporters or the obituaries they may write that will offer the final verdict on his actions, he said, but future scholars who will study them in the context of their day.

“I’m not saying that everything I did was right,” he said, “but everything I did was for an honorable purpose. I had to do some nasty things, locking fellows up without trial.”

And although the leaves are already falling from the tree, he said, the Lee Kuan Yew story may not be over yet.

He quoted a Chinese proverb: Do not judge a man until his coffin is closed.

“Close the coffin, then decide,” he said. “Then you assess him. I may still do something foolish before the lid is closed on me.”

Copyright The New York Times